Q: what are pie-weights?

A: they woam the seas in search of pwunder.

Dec 27, 2011

gwoan

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Dec 23, 2011

the ice cream business

I couldn't tell them much other that it is as important to be lucky as it is to be good. And it is also important to love what you do. I think that over the years one of the most important things I've observed in the ice cream industry is that it is filled with people who love what they do. There is something to be said for being involved in an industry that makes people happy.

howard waxman

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

time

you, or at least i, would imagine that a library would stay open regular hours instead of closing at noon the day before it shuts down for a whole week.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Dec 12, 2011

pattern

A pattern has an integrity independent of the medium by virtue of which you have received the information that it exists. Each of the chemical elements is a pattern integrity. Each individual is a pattern integrity. The pattern integrity of the human individual is evolutionary and not static.r. buckminster fuller, synergetics: explorations in the geometry of thinking (505.201).

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: instruction, scalefree, technology, theory, translation

Dec 11, 2011

Dec 10, 2011

Dec 3, 2011

Nov 28, 2011

limitation

a discussion in the car during a long drive back from new hampshire brought this back to top of mind, where it should really always be.

One tires of living in the country, one moves to the city; one is tired of one's native land, one travels abroad; one is europamüde, one goes to America, and so on; finally one dreams of traveling endlessly from star to star. Or the movement is different but the same. One tires of porcelain dishes, one dines off silver; one tires of that, one dines off gold; one burns half of Rome to get an idea of the conflagration at Troy. This method defeats itself: it is the bad infinite. What did Nero achieve? Antonine was wiser; he says, "It is in your power to review your life, to look at things you saw before, from another point of view."also relevant: renunciation, words from a totem animal, hugh of st. victor, the inner chapters, little gidding, and ithaka. below, the original german:

The method I propose consists not in changing the soil but, as in the real rotation of crops, in changing the method of cultivation and type of grain. Here, immediately, we have the principle of limitation, which is the only saving one in the world. The more you limit yourself, the more resourceful you become. A prisoner in solitary confinement for life is most resourceful, a spider can cause him much amusement.

søren kierkegaard, either/or

Diese Wechselwirtschaft ist die vulgäre, die unkünstlerische, und hat ihren Grund in einer Illusion. Man mag nicht mehr auf dem Lande leben, und reist deshalb in die Residenz; man mag nicht mehr in seinem Vaterlande leben, man reist ins Ausland; man ist »europamüde« und reist nach Amerika u.s.w.; man schwelgt in der schwärmerischen Hoffnung einer unendlichen Reise von einem Stern zum andern. Oder die Bewegung nimmt eine andre, wenn auch noch extensivere Richtung. Man mag nicht mehr von Porzellan essen, man ißt von Silber oder von Gold; man brennt das halbe Rom ab, um den Brand Trojas zu sehen. Diese Methode hebt sich selber auf. Denn was erreichte Nero? Nein, da war Kaiser Antonio klüger, er sagt: anabiônai soi exestin; ide palin ta pragmata, hôs heôras; en toutô gar to anabiônai.

Die Methode, die ich vorschlage, liegt nicht darin, daß man immer neues Land nimmt; man würde dann auch bald am Ende sein. Die wahre Wechselwirtschaft besteht darin, daß man bald diese, bald jene Methode wählt und mit der Saat wechselt. Und da haben wir auch gleich das Prinzip der Beschränkung, das einzige, welches uns retten kann. Je mehr man sich selber beschränkt, um so erfinderischer wird nun. Ein Gefangener, der sein ganzes Leben in einsamer Zelle zubringen muß, von allen andern Gefangenen abgeschlossen, ist sehr erfinderisch; eine Spinne kann ihm die größte Unterhaltung sein. Hier haben wir das Prinzip, das durch seine Intensität, nicht durch seine Extensität Befriedigung sucht.

Posted by

vaughn tan

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: art, books, craft, epistemology, execution success, instruction, intransigence, intuition, moral fibre, process, sustainability, theory, work

Nov 27, 2011

Nov 15, 2011

a step forward

Going back to a simpler life is not a step backward.on this, also see the old days.

yvon chouinard [thx josh]

[The Tarahumara] know that every step forward, every convenience acquired through the mastery of a purely physical civilization, also implies a loss, a regression.

antonin artaud

Preparing things simply is deceptively difficult, since there is no way to cover up our mistakes.

edward espe brown

Understanding evolves through three phases: simplistic, complex, and profoundly simple.

william schutz

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: complexity, epistemology, execution success, intuition, moral fibre, sociology, sustainability, theory

Nov 13, 2011

a marvellous stage

From the age of six I had a mania for drawing the forms of things. By the time I was fifty I had published an infinity of designs, but all I produced before the age of seventy is not worth taking into account. At seventy-five I have learned a little about the real structure of nature—of animals, plants and trees, birds, fishes, and insects. In consequence when I am eighty I shall have made still more progress. At ninety I shall penetrate the mystery of things; at a hundred I shall certainly have reached a marvellous stage; and when I am a hundred and ten, everything I do—be it but a line or dot—will be alive.on this, also see the true names of things, wheatcakes, and a certain atlas.

katsushika hokusai

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: art, complexity, epistemology, execution failure, execution success, intransigence, intuition, scalefree, transient

Nov 9, 2011

freedom, and how you can achieve it

you, like me, could soon be free of the iphone's tyranny and AT&T's colossal rip-off cellular service (so bad it would be laughable if it weren't also tear-inducingly frustrating, inconvenient, and expensive).

update: t-mobile unlocked the phone after 60 days of active service.

update: grooveip works fine. it is a bit buggy but i use voice sufficiently infrequently that it doesn't matter to me. (last month, my total talk time was 33 minutes using both the t-mobile network and grooveip). jacob h-a has been fooling around with a combo of sipdroid and pbxes.org that he says is working out well for him. no doubt he'll send an update once he's figured it out completely.

- i will save about $53/month ($1250 over 2 years) in service costs compared to renewing my 2-year AT&T contract. my total startup cost was $252.37, my monthly payments will be no more than $30.

- i don't have to tell everyone and their dog what my new number is—they call the old numbers, my new phone rings. all my voicemails and text messages can go to email if i desire it.

- i can travel easily with my phone without extortionate roaming fees.

- once i unlock the phone, i can discontinue service at any time and resume it with t-mobile or any other provider with almost no disruption in how people call me or send me text messages.

there is much conflicting information on the interwebs about setting up this brand new wal-mart t-mobile plan. there are hundreds of phones, most of which suck for one or more reasons (on which, see below). consequently, setting up the phone and related services took 4 hours of research instead of 15 minutes. finding the phone took weeks of research.

we stand upon the shoulders of those who go before us (or, more precisely, those who stand underneath us). below, i provide excruciatingly precise detail on what to buy, where to buy it, and how to do everything you need to do to replicate my current situation of cellular bliss—all in the interest of human progress and freedom from digital tyrannies. and because i care about you.

- use data intensively and send text messages all the time

- barely use voice calling

- are off contract with your current cell service provider

- have a google voice account

- don't really need domestic data roaming

- a final caveat: you may face a termination fee if you port your phone while your contract is still in force. google voice's porting process may get fubar-ed (horror stories abound). in the grand scheme, these are minor annoyances for which i claim no responsibility.

- get a phone: purchase an off-contract prepaid-service t-mobile samsung exhibit ii 4g at wal-mart or online (see below for why it is the best compromise phone available today). amazon has the cheapest handsets and fastest fulfilment too. if you want to be nice to me, buy it through this link. important note: you cannot purchase your phone or activate it in a t-mobile physical store location if you want the $30 unlimited data plan described above. while the plan is marketed through wal-mart, it appears to be one of the t-mobile monthly4G plans and is available on any newly activated monthly4G SIM card, as long as activation happens on t-mobile.com.

- switch the phone on: when your phone arrives, insert the SIM and battery and begin to charge the phone.

- activate cell service with t-mobile: have the ugly pink box handy and go to t-mobile's prepaid service activation page. enter the activation code (on a card inside the box) and the IMEI and SIM serial number (both listed on a sticker on the box), choose the $30/month prepaid plan with unlimited data, and complete your activation process but skip step 5 (funding your account). write down the new phone number which t-mobile assigns to you.

- fund your account: buy your account minutes from callingmart instead, which often has standard discounts on t-mobile prepaid service, in addition to a host of coupons (like these). again, if you want to be nice to me, please use this link to buy your minutes from callingmart.

- forward google voice to your new t-mobile number: go to this page and click on the link to "add a new phone"

- port your current cellphone number to google voice: if you are with AT&T, find your AT&T account number and PIN number ready, as well as the exact address and telephone number AT&T has on file for you (you should sign into your account at AT&T to check all this). then, go to this page, click on the link to port or change your number, and follow the quite clear instructions. if, despite entering the exactly correct account number and other details, the google voice workflow tells you to "Please fill out all of the required fields," be persistent and check for extra spaces and that you have the correct case. once you get to google checkout, pay the $20 port fee and confirm the port request. (you will note that there is no field to enter your AT&T PIN.)

- wait for the porting error message and fix it: eventually, google voice will send you an email titled "Oops! Issue with your Google Voice Number Porting Request." click on the link in the email and enter your AT&T PIN number.

- make your current google voice permanent: when the port is completed, you'll get an email titled "Google Voice Number Porting is Complete!" rejoice, then go to google voice again, click on the link to "make permanent," follow instructions and pay another $20.

- unlock your phone: if you purchased your phone for full price, you can request that it be unlocked immediately. full details here.

- bask.

THE STORY

- it's locked to AT&T forever. i took a second phone with me whenever i was out of the country, so i would not be subject to AT&T's ludicrous roaming prices.*

- the silent-mode toggle switch is broken, but works unpredictably. this is always awkward in meetings.

- there is no way to shut off the shutter sound on the iphone camera without resorting to jailbreaking and doing other silly workarounds.*

- the battery life seriously blows.

- dropped calls all the time. all. the. time.

- i regularly used a small fraction of the hundreds of minutes i paid for on even the least expensive AT&T iphone plan.

- screen too big = device is enormous (bigger than iphone)

- screen too crappy

- looks like a sex aid

- way too expensive (>$200)

- CDMA-only

- not 4G-compatible in the US

- not world GSM-compatible

- processor slower than molasses

- obnoxious colour

- no front-facing camera

- not warrantied in the US

- battery cannot be replaced by user

- lousy battery life

- soon-to-be obsolete operating system

- locked to one carrier

Posted by

vaughn tan

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: enough, execution failure, execution success, intransigence, iphone, process, technology

Nov 8, 2011

a mystery apple

this time of year, there is nothing more wonderful to eat than late-ripening, fresh-picked, crisp, crunchy apples. the early apples are still decent but are growing mealy after over a month of storage.

the apple of this very moment is either a brock or a northern spy—so say the labels on the apple bins at the kimball farm stand at which i have been buying these apples. the problem is: most variegated red apples look the same to my untutored eye (apple nerds, please withhold judgment).

the apple itself is about the size of a softball, a little flattened, with shallowish floral and stem depressions where there is some russeting (but not much). a little bit of ribbing, but inconsistent across the four specimens so far. it's yellow-green with zones of transparent red (the two i have here are speckled all over with little bits of russeting), the flesh is bright white with green tints close to the skin. the peel is tight and snappy under your teeth, the flesh crunches, the juice is abundant, there is sugar, there is much acidity, there is a bit of sap and quite a lot of mouth-clearing tannin, there is the flavour of a good oolong tea. it's winey, the way a winesap is.

update 1 (11.7.2011): happened on another of these incredible mystery apples in the back of the high-humidity zone of the refrigerator. the red zones on this one are so transparent they look almost orange. the apple is of medium-large size, and have little russet flecks all over that i have since learned are lenticels. it tastes just as described above, and the acidity and tannins dry my mouth out just enough that i want to eat these all year. this apple looks just like a brock, inside and out. thinking that i'd stumbled upon the answer, i took a known brock and sliced it open. you can imagine my disappointment when the two apples that looked alike tasted nothing like each other. the one i know to be a brock is insipid and has a crunch filled with initial conviction but lacking, unfortunately, in stamina. could it be a macoun, at the height of its season, a revelatory apple? the search continues. i must find a pomologist.

update 2 (11.7.2011): mystery apple photos!

update 3 (11.8.2011): though it was painful to do so, i left a slice of yesterday's mystery apple uneaten, to see how quickly it would oxidise and to what extent. the result: very little browning after 30 minutes, no additional browning even after 24h.

update 4 (11.8.2011): another of the mystery apples! perhaps, anyway. this one is labeled king luscious, but has the same flavour profile as the other mystery apples (see above). trouble is, it is not massive, and the red portions of the peel are more orange than the blue-cast red of the king luscious. i begin to suspect that the labels on the bins at the market are part of the problem.

Posted by

vaughn tan

5

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: apples, execution success, food, fruit

Nov 7, 2011

convergence

it's great when your ethics and your hedonism converge.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: decisions, epistemology, execution success, food

Nov 4, 2011

Oct 31, 2011

monday morning

barismo el bosque, melitta/193F; royal copenhagen blue fluted remix.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: coffee

Oct 29, 2011

Oct 28, 2011

mindful eating

Eating is often a knee-jerk reaction: we cook and eat what is most convenient, what is least expensive, what appears to taste good. But deciding what to eat involves consequences that are wide-ranging and long-lasting, even if we don't recognise what those consequences are. We can make good decisions about what actions to take only by knowing the consequences of those actions. And we can only know these consequences if we investigate, inquire, and gather more information.

Meat is a good example. Meat is environmentally costly. Most easily available meat is intensively raised and processed in operations that raise ethical and food-safety concerns in addition to the environmental ones. Learning more about meat production allows you to make better decisions about the meat you choose to consume. You may choose to eat less meat, and buy what meat you do eat from producers who claim to raise and process the meat in ways that minimise the risk of food-borne illness. In doing so, you are choosing to eat not the least expensive or most convenient meat, but rather the meat that is produced with attention to health or environmental impact. Or you may continue eating the meat you've always eaten, with a better knowledge of the risks that you are exposed to.

Another example: You go to eat at a very good restaurant. The food has been made with care from good ingredients. The check comes—it is for a staggering amount. Yet the prices, though high, are subsidised by chefs, stagiaires, and producers who work long hours for little money; there is not much profit in food sourced and made with care. Fast food, in contrast, is inexpensive. It is often made with indifferent ingredients and by poorly paid workers. There are considerable profits to be made from fast food. Questioning what goes into the price of the food you eat may make you decide to cook for yourself most of the time and to eat out infrequently and only at restaurants that cook with care. Or it may not.

All this has been said before. Being mindful of the consequences of eating sounds like submitting to nothing but limitation, restrictions, and unaffordable food. Acknowledging, for instance, that eating food grown far away seriously damages the environment means for the most part restricting the food you eat to things grown locally—a smaller and less predictable selection.

But the limitations imposed by mindful eating are not the full story.

Questioning what, how, and why we eat limits us in some ways but also opens up new possibilities. Limitations are like frames that, by excluding much of the view, allow you to look more closely at whatever is within the frames. If you decide to eat only local, seasonal fruit, you have no choice but to begin to pay close attention to the fruit that is around you. But you come to realise that strawberries taste different from day to day as the season progresses, that there are in fact different varieties of strawberries that ripen at different times, and you begin to eat strawberries only when they are at their very best.

Asking questions about the food you eat can lead you to discover techniques and methods of cooking and flavour combinations that are new to you but well-known elsewhere and to other people. For cooks, asking questions and finding answers is a way to learn how to express a particular sense of what tastes good and what is good to eat. It is also a way to develop that particular sense, the style of cooking that distinguishes you from other chefs—a way to develop a vocabulary for communicating your values in food, the reason why you cook.

We should ask ourselves a multitude of questions about the food we eat. Our decisions about food will be informed by the answers we find. The point is not to find the single right answer to each question (it doesn't exist) but rather to begin to ask the questions.

Posted by

vaughn tan

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: epistemology, food, intuition, moral fibre, process, sustainability, technology, translation

Oct 27, 2011

he's dead, jim

jim leff on why mediocrity is ubiquitous. please read and respond.

Posted by

vaughn tan

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: care, complexity, execution failure, execution success, food, intransigence, intuition, sustainability

the world is concurrent

The world is concurrent. Things in the world don't share data. Things communicate with messages. Things fail.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: complexity, execution failure, execution success, intransigence, sociology, theory

Oct 25, 2011

Oct 24, 2011

Oct 23, 2011

Oct 20, 2011

Oct 19, 2011

Oct 18, 2011

Oct 12, 2011

Oct 11, 2011

food aversions

when push comes to shove, you eat. in the course of research, i’ve been handed ants, raw lamb brain, cooked lamb brain, fermented shark, and a live fjord shrimp to try. the shrimp, which comes with slowly moving feelers and scrabbly legs, feels a lot like what i imagine a live cricket would feel like in your mouth. it’s quite delicious though, and crunchy. there goes another food aversion.

about the fermented shark, the less said the better.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: food

Oct 9, 2011

Oct 8, 2011

Oct 7, 2011

change is our only constant

new tires, new brakes, new saddle, new bartape, same old frame.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Oct 5, 2011

commemoration

tonight, google commemorated steve jobs by changing its homepage and adding what used to be called a homepage promotion in every language google.com is available in: a link under the search box. (the link points to apple.com, a beautiful gesture in itself.)

the amount of traffic to the google homepage makes it tremendously valuable real estate, and that promotional spot is fiercely protected because it is so closely associated with the google brand. homepage promotions go through many rounds of approval because so many people see the homepage every day. because of that little line under the searchbox, tens of millions of people (at least, maybe over a billion, depending on how long the link stays up) around the world will know of steve jobs's passing. it's hard to imagine a more effective way to spread the word. the homepage promotion went up within a few hours of the apple announcement and i'd like to think that the phone call that did it came out of a flurry of emails up top and didn't go through weeks of the usual approvals and clearances.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Oct 4, 2011

a new book

opinions differ on dessert. is it meant to be a comforting, sweet, predictable ending to a good meal, or is it meant to be unsettling and to provoke the eater into a consideration of new flavours? i fall into both camps, depending on the day. especially at restaurants on the cutting edge, i incline to the latter. below you see a dessert which is so much on the cutting edge it may have gone slightly beyond it.

the pleasure of a good brioche is not primarily in the buttery flavour or the lightness of the baked bread. rather, it is in the gentle aroma of yeast left over from a long, slow fermentation. this dessert plays on this yeast smell and connects it to similar musty aromas in blackberries and corn. it consists of grilled corn kernels shaved off the cob and bound with blackberry puree, a tart blackberry sorbet, young nasturtium leaves for acid, and a frozen foam made of heavy cream infused with yeast.

the yeast cream parfait is aerated by warming the infused cream slightly, then placing it in a valve container and drawing a vacuum on it in a chamber vacuum. the water begins to boil at a relatively low temperature creating a fragile foam, at which point the vacuum is released. the foamed liquid in the container is kept under partial vacuum because of the valve and the whole is placed into the blast freezer to freeze while still aerated. this fiddly procedure produces blocks of a white sponge that tastes of brioche and which disappears in the mouth.

one comment about this was particularly apposite: "many desserts take pages out of old books. this dessert is like a new book completely. perhaps diners are not quite ready for this. after a meal of new and uncomfortable textures and flavours, they might be expecting something familiar and sweet. for diners like that, this is like a big 'fuck you.'"

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: complexity, copenhagen, execution success, food, intransigence, process, theory, translation

Oct 3, 2011

Oct 2, 2011

you can change your life

There are two ways of looking at the work you do to earn a living:

One is the way propounded by the late Henry Ford: Work is a necessary evil, but modern technology will reduce it to a minimum. Your life is your leisure lived in your ‘free’ time.We opt uncompromisingly for the second way.

The other is: To make your work interesting and rewarding. You enjoy both your work and your leisure.

There are also two ways of looking at the pursuit of happiness:

One is to go straight for the things you fancy without restraints, that is, without considering anybody else besides yourself.We, again, opt for the second way.

The other is: to recognise that no man is an island, that our lives are inextricably mixed up with those of our fellow human beings, and that there can be no real happiness in isolation. Which leads to an attitude which would accord to others the rights claimed for oneself, which would accept certain moral or humanitarian restraints.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: complexity, execution success, sustainability, theory

Sep 28, 2011

solution

By the next day at lunch, Kant and Wittgenstein had dissolved in the marinara on the fifty-cent spaghetti plate at Romeo's. I returned to Rimbaud, Apollinaire, and Char for wisdom, abandoning forever the academic pursuit of trying to answer questions that no one ever asks.more jim harrison here.

jim harrison, "principles" in the raw and the cooked

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: books, execution failure, execution success, food, intransigence, intuition, theory

duck duck goose

the only advantage of reading on a barren patch by the river is that it is relatively free of goose shit.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: cambridge

Sep 22, 2011

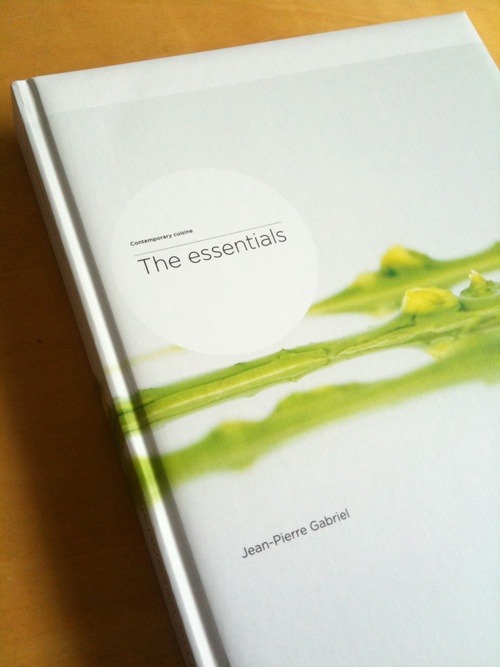

this just in

a battered box from belgium arrives, its contents fortunately unscathed. the essentials (unilever, 2009) is lavishly illustrated and filled with commentary and recipes from a slew of dutch chefs. at first glance it appears to be a precursor to modernist cuisine. more later, after a much longer look.

[thx, j-pg]

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

how chefs can (help) save the world

Though lacking a grand theme, a common thread ran through Planting Thoughts, a food symposium held in Copenhagen in late August that promised serious thinking and discussion about food. Good food, the diverse crowd of speakers (chefs, food scientists, farmers, biologists, foragers, and more) argued, takes time and effort from everyone involved in making it: There are no short-cuts. The symposium also showed how haute cuisine—often derided as elitist—can support efforts towards building a system that can make enough good, sustainably grown food for everyone and make it accessible to all.

Most obviously, haute cuisine can extend and reinvigorate local food culture and history, the context of people, places, stories, and traditions that surrounds food in a given place. Fine dining restaurants can afford to pay a premium for what we now think of as artisanal ingredients, keeping them in production and their producers in business. Less obviously but more importantly, many chefs use culture and history when creating new dishes in their restaurants. Japan's Yoshihiro Narisawa, Italy's Massimo Bottura, Spain's Andoni Aduriz, Australia's Ben Shewry, Daniel Patterson from the United States—they all use the historical and cultural context in which they work to help them answer the question: "This was what came before, what should we cook next?"

Patterson's food is an example of how culture and history can point chefs in the right direction. He often researches how particular ingredients have historically been cooked, then bases novel interpretations on what he finds. At the symposium, he showed three beet dishes in which he took the familiar texture of the roasted beet (from the roasted beet and goat cheese salad that was introduced in the late 1970s and is now ubiquitous) and transformed it into something new but—crucially—not forbidding. Here's one: roasted beets on a rose-scented snow with yogurt, a novel pairing of flowers and earth, united by the familiar combinations of floral/milky and earthy/milky flavors. Chefs like Patterson create new and delicious things by returning to what we already know. For them good food is anchored in context, and requires investigation of place, time, and history.

Clearly, the labor-intensive food these chefs make will never be the food of the people. This is why haute cuisine seldom participates in discussions about how to feed many people sustainably and healthfully. This is a false divide. Even if the food itself does not scale up from the fine dining restaurant, the approach—examining context more closely—could be part of the solution.

Looking to history and culture helps us understand why we eat the way we do today. Thousand of years of food choices have led us to eat mostly starches from a few cultivated plants instead of the diverse set of foods that we used to eat. This modern, developed-country way of growing food and eating has expanded dramatically in the last half-century. Accelerating urbanization and changing work patterns during this time have made it less likely that families cook and eat together. Now, it's the exception rather than the rule to eat good food made with care, that originates in a place and with people that you know, part of a culture and history that you share. "You would think that at the end of thousands of years of development, it would take a long time to destroy these memories of good food," Patterson said, "but industrial agriculture took that all away in a generation, wiped it all out."

Our food production and distribution system is a litany of connected problems. We grow more food per capita than we need, but we grow the wrong food, in the wrong places, in the wrong way. On average, we consume more calories than we require. Industrial agriculture produces trillions of calories but at tremendous and mostly hidden cost. The energy spent in manufacturing the fertilizers and pesticides, operating the machinery, and fueling the transport required for industrial agriculture is hidden in subsidies on agriculture, fuel, and transportation. Our starchy diet is associated with chronic health problems that we pay for indirectly with taxes and overloaded health-care systems. When cheap energy finally becomes too expensive and the chronic health crisis can no longer be ignored, what we choose to eat and how we we grow, process, transport, prepare, and sell it will have to change.

What, then, might the future of food look like? About the only certainty is that it will have to be built from a lot of smaller solutions rather than a single industrial mega-solution. Hans Herren, an author of the IAASTD (an international review of agricultural knowledge), noted that small-scale organic farming is as productive as the world average for agricultural production, and challenges the widely held assumption that mechanized, industrial agriculture is the only viable solution. While too many people live in urban areas for all agriculture to be local, Thomas Harttung, an urban agriculture advocate, suggested that urban agriculture can produce an enormous volume of food to supplement our food supply. The foragers who spoke at Planting Thoughts, Miles Irving and Francois Couplan, also argued that wild foods are diverse and plentiful enough to be as meaningful and delicious a part of our food supply in the future as they were in the past. Diversifying our food production systems is critical, and this means including elements based on old ways of doing things like foraging and local, organic production methods, but with the advantage of new knowledge.

Changing how we produce, distribute, and consume food will require us to unlearn what we take for granted now: apparently cheap food, reliance on starches, unnecessarily abundant calories, eating a lot of meat. Then we'll have to learn something new: spending time and effort to find and make real food, growing and eating closer to home, eating less but better, eating more plants. This will be tremendously difficult. A change in our food system won't happen if it isn't supported by an equally radical change in our food culture.

Change, though, is easier if it is delicious and pleasurable—and this is where haute cuisine comes back into the picture. Chefs are, as Michel Bras called them, "marchands de bonheur," their know-how employed in making delicious things. This knowledge gives chefs the ability to use pleasure to help change what people want to eat. "Poor choices lead to unsustainable foods," Ben Shewry said. "The responsibility of the chef is to know and to act." Activists for sustainable food and food access rightly emphasize how urgently we need to change our food system. Chefs can help make that change delicious and desirable, not just necessary and inevitable.

click here for other posts about Planting Thoughts, including session summaries.

[this post was cross-published in The Atlantic|Life]

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: biology, complexity, copenhagen, decisions, execution success, food, government, history, instruction, planting thoughts, sustainability, technology, theory

Sep 20, 2011

reason

So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable Creature, since it enables one to find or make a Reason for everything one has a mind to do.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: intransigence

Sep 19, 2011

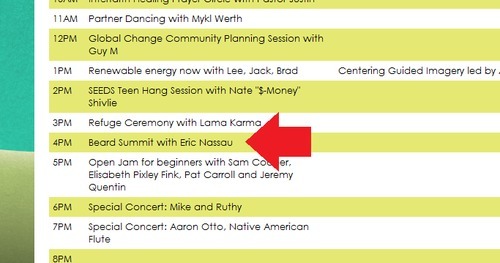

the hard truths

jd: let's go to this

vt: i won't fit in. i don't have a massive beard.

jd: see below.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Sep 18, 2011

sofra

L-R: baba ghanouj, muhammara, beet tzatziki, tomato kibbeh

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: cambridge, execution success, food

Sep 15, 2011

Sep 12, 2011

planting thoughts: session 4, sunday p.m., 8/28

michel bras (chef at bras, laguiole)

vivre la cuisine

for michel bras, quality is a whole activity: it encompasses the cuisine, the ingredients and how they are grown, the architecture of the restaurant, how the staff are treated. the iconic gargouillou of individually cooked young vegetables is "a state of mind" emblematic of bras's approach to cooking. it changes with the vegetables, plants, and flowers that are available, and is his way of communicating through a dish the feeling of being in nature and of being aware of the season. bras calls the gargouillou "a way of looking at nature," an expression of the decades-long relationships he has with the farmers in his part of france, a statement of his belief that it's valuable to sometimes concentrate on what is perfectly ready in the moment. chefs are "marchands de bonheur," their task to produce emotion, delight, and joy in the diner, regardless of the type of food they make. a correctly prepared gargouillou is laborious but transmits a sense of joy in time and place to the diner. food can have the same effect even if less elevated: a tartine of bread selected with care for the right proportion of crust to crumb, just enough shaved chocolate, a few red berries, and a milk skin--simple, delicious pleasure.

harold mcgee (author)

the flavours of plant life

"plants," harold mcgee says, "are the chemical masters of the universe." the chemicals they produce from rocks, air, sunlight, and water make them taste different and, in some cases, delicious. these chemicals serve different purposes. the flavours and aromas of fruit are designed to attract and please animals; in a sense they are complex pre-cooked foods made by plants to be eaten. the flavours we associate with herbs and spices, on the other hand, are often chemical weapons plants produce in response to their environment. understanding the logic of this plant biology and chemistry helps chefs cook better. for instance, the undesirable green and grassy aromas in herbs are produced when the leaves are damaged and the chlorophyll in them breaks down. knowing that the desirable aromas are from oils in hairs on the leaves, slapping the leaves rather than cutting or crushing them produces an aroma with more desirable than undesirable notes. knowing that flavours are essentially a plant's response to the environment may also support the quality claim that organic agriculture makes. use of pesticides and herbicides reduces the stress crop plants experience and, if flavour and aroma compounds are plant responses to stressful environments, possibly makes them less flavourful as a result.

david chang (chef at the momofuku restaurants, new york)

food microbiology: an overlooked frontier

david chang claims that he didn't do well in school--"cooks are allergic to learning and scientific terminology"--but regrets it now. the most exciting projects at momofuku now center on learning how to use microbes to produce more delicious food. one misconception about food is that bacteria and fungi are bad. other than the yeasts and bacteria that make bread, beer, and wine, we think of other microbes as pathogens. yet, microbes can transform raw ingredients in an almost infinite number of ways. microbial growth on food is so affected by local climate and microbe populations that we should think of the flavours of microbial activity almost as another form of terroir. chang and dan felder, who runs the momofuku test kitchen, illustrated this with what they call pork bushi (inspired by katsuobushi, the inoculated, dried bonito that is ubiquitous in japanese cooking). they prepared pork the same way fresh bonito would be prepared for katsuobushi and were surprised when the usual aspergillus molds didn't take hold on the pork. instead, in the new york city air, yeasts from the pichia family flourished on the pork and produced savoury flavours similar to katsuobushi. but they weren't able to get consistent results until some professional microbiologists helped them refine their pork bushi production protocols. chang's goal as a chef is to keep learning more and, these days, learning more often requires chefs to move out of their comfort zone and challenge themselves by returning to the scientific method.

andoni aduriz (chef at mugaritz, guipuzcoa)

natural and cultural ecosystems

at mugaritz, andoni aduriz says, they try to work with what they have, to take the time to respond rather than try to control. taking time and care produces a special product worth waiting for. mugaritz is connected to the place in which it exists by relationships with suppliers, local history, and local culture. for example, the idiazabal cheese that they buy is endangered, the latxa and carranzana sheep from which milk idiazabal is historically made are wild-pastured and less productive than barn-raised sheep--mugaritz's commitment to buying and producing locally is, to aduriz, a critical form of historical and cultural support that keeps communities and traditional ways of doing things alive. what they buy is not only the flavour of these foods, but the time and care expended, the history and culture embodied in them. "our food is very simple," aduriz said, "we like to eat stories."

gaston acurio (chef at astrid y gaston, lima)

the power of food

food has the power to change things--gaston acurio has seen it happen in peru. the new peruvian cuisine began with chefs rediscovering peru's enormous biodiversity. peruvian chefs learned to stop hankering for products from other parts of the world: "using our biodiversity on our own plates felt like a scream of freedom." but after they'd found local ingredients that tasted good, they began to be concerned with justice for food producers, with food access for the poor, and with health. they realised that peruvian cuisine becomes sustainable only if all these pieces are in place--when client, chef, and producer alike are happy. they developed free schools where chefs taught people to cook to change their livelihoods, worked with producers to fight big businesses that were polluting the rivers and fields where food was grown. "all this is accomplished by the power in our hands," acurio said, "there is no limit to what food can change."

other posts about planting thoughts:

planting thoughts: a symposium without dissenting views,

summaries: session 1, session 2, session 3

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: care, complexity, decisions, epistemology, execution success, food, intuition, moral fibre, planting thoughts, sustainability, technology

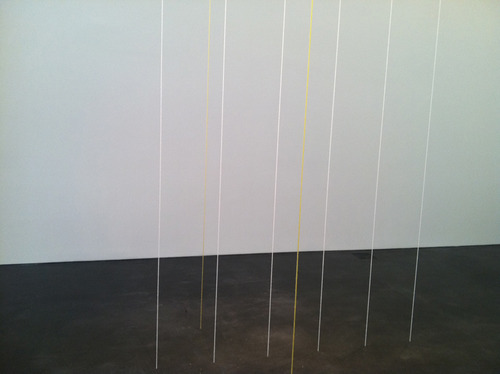

our denver correspondent

ben sends a photograph of a sandback installation at mca denver; show looks good. for more sandback, also see here and here. might want to check out ben's work too.

Posted by

vaughn tan

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: art

planting thoughts: session 3, sunday a.m., 8/28

stefano mancuso (director, international laboratory for plant neurobiology)

the unexpected plant: beyond the animal model

we should re-examine our preconceptions about plants as unthinking, unmoving things. stefano mancuso explained how plants are able to sense and respond to changes in their environment with more precision and sophistication than we expect. some plants (like sunflowers) appear to learn how to respond to the environment collectively, so that they may be thought to be social organisms. plants have also evolved together with the animals that live around them (including humans). they make use of animals to reproduce and protect themselves, using tasty fruit to induce animals to transport their seeds or protect them from other animals. we might, for instance, think of domesticated plants such as wheat or corn as having trained humans to protect and propagate them with enormous success. plants have also developed remarkable systems for protecting them from threats in their environment: the chemicals plants produce repel insects, warn nearby plants of imminent attacks insects, and also happen to sometimes taste good to humans.

alex atala (chef at DOM, são paulo)

insects and plants: together for life

eating insects seems unfamiliar and scary, alex atala said, but everyone who has ever eaten strawberry yogurt has eaten insects in the form of a red dye which is extracted from cochineal beetles. we seek the familiar because our experiences only make sense in terms of what we have experienced before. he distributed cubes of unflavoured agar, each containing a piece of the amazon: a single amazonian ant. many people in the audience thought it tasted of lemongrass and citrus but atala pointed out that to people who have grown up eating those ants, lemongrass and citrus taste like ants. atala's point was that we should not take for granted culturally defined rules of what should and should not be eaten. "to understand a flavour better," he said, "we must take ourselves away from the familiar." after cooking for years in european restaurants, he realized he had to go back to brazil to explore the then-unknown flavours of his country, rather than trying to cook the food of a different part of the world. his restaurant in brazil now uses the amazon as a source for new and unfamiliar ideas and ingredients that even most native brazilians have never had the opportunity to taste--raw propolis-filled rainforest honeys, spontaneously fermented sugarcane vinegars, a panoply of forest herbs and plants, and others. the enormity and diversity of the country-spanning amazon paralyzes what atala calls "the sophisticated world": in dogshead, one relatively small part of the amazon, there are 23 ethnicities, 21 languages, and over 300 varieties of domesticated plants that are not known outside that region. the amazon as a whole is "a world of flavours remaining to be discovered." atala's understanding of the region's foods comes from natives whose knowledge is anything but simple. atala increasingly believes that our efforts to preserve nature must also include plans to preserve peoples and cultures, or rich stores of local knowledge and practices will be lost.

francois couplan (ethnobotanist, author)

wild plants and culinary creativity

80,000 wild plants are known to be edible and were once eaten--a balanced, diverse, interesting, healthful diet. we've forgotten about most of these wild plants because of the rise of agriculture, and because eating wild plants used to signal low social status. couplan believes that there is a fracture of the wild and the civilised that is leading us to unbalanced, monotonous diets that depend too much on cultivated plants and which make us sick. our diets will improve if we are able to be opportunistic in combining both farmed foods and foraged foods, gathering what we can, when we can. this can only happen if more people learn about how edible wild plants can be used. this, couplan believes, is where haute cuisine comes into the picture. he has taught chefs in france and the rest of europe how to identify, gather, and use wild plants in their restaurants. "when chefs start using plants," he said, "they become stars and are not anymore despised. people begin to want to learn about them."

massimo bottura (chef at osteria francescana, modena)

never stop planting

trapped in new york by hurricane irene, bottura sent a video (subtitled version available on eater) and a statement instead. bottura believes that food should be an object of contemplation, not just one of consumption. we've turned into lazy eaters, pursuing pretty, superficially satisfying foods that are sweet, smooth, and unctuous. challenging food changes those who eat it, bottura thinks, and chefs should be helping people learn to eat challenging food again. to do this, chefs have to acknowledge that food is not only about aesthetics but also about ethics. cooking ethically means going back to the source of ingredients and influences, and acknowledging the culture and history from which the food comes. without these creation stories--stories from friends, suppliers, customers, neighbours--food loses its connection to place, time, and people. without being aware of this connection and reflecting it in, the chef's job is incomplete. "food is one of the strands of the cultural braid that binds us," bottura said "our business is not only about serving people food. that is only the final act."

søren wiuff (farmer)

all that we eat has been alive

søren wiuff changed how he farmed years ago when he realised that he couldn't make money farming industrially even though his farm was highly productive. he went back to doing things as his father did: by hand and with care, "learning what will grow in the garden, feeling your body as part of harvesting something." his close connection with the crops he grows led him to question many of the assumptions farmers usually have about what they grow and how they grow them. he gradually learned how to respond to the unpredictable, changing nature of the living things on his farm rather than trying to force them to fit into a recipe, a formula, a set of preconceptions. this has led to his accidental discovery of new crops: sowing leeks later in the season than usual (so late that wiuff thought the cold would kill them) led him discover baby leeks that sprout in april of the following year, or tasting the usually discarded aerial bulbils of mature leek plants. he credits this partly to support from working with chefs--like those at noma--who are open to trying these new and unfamiliar ingredients and making delicious things out of them. "it's like having playmates," he said, "they make me good by respecting that i'm a farmer. if someone tells me i'm doing something good, i do better next time."

molly jahn (univ. of wisconsin and commission on sustainable agriculture and climate change)

how good food can save our planet

people have to demand healthy food systems for them to take hold and become successful. when molly jahn was working as a plant breeder, she collaborated with organic farmers to develop a new variety of delicata squash that was delicious and more pest-resistant. she targeted organic farmers and chefs in her her efforts to promote the variety, and realised that the variety became successful when chefs demanded it, put it on their menus, and exposed it to consumers. much later in her career, when she had begun to work on agricultural policy in wisconsin, she helped a group of potato farmers in the state develop a stringent integrated pest management and certification program (eco-grown) to protect wildlife on and around their farms. though the program was successful in its environmental goals, she thinks that it never achieved commercial success because chefs were not as involved in its promotion. jahn's message to chefs was simple: "chefs help accelerate people's valuation of good, responsibly produced food."

other posts about planting thoughts:

planting thoughts: a symposium without dissenting views,

summaries: session 1, session 2, session 4

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: agriculture, complexity, copenhagen, decisions, education, food, government, planting thoughts, research, sustainability, technology

Sep 11, 2011

chicken and waffles

chicken sausage, red carrot, and potato hash, fried egg and chives, waffle cone, chili ketchup, american flag. at toscanini's, where breakfast now comes only one weekend a month.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: cambridge, execution success, food

Sep 10, 2011

planting thoughts: session 2, saturday p.m., 8/27

kamal mouzawak (founder, souk el-tayeb)

make food not war

"difference," kamal mouzawak believes, "can be a reason for war or a celebration of diversity." his producer-only farmers' markets in lebanon attempt the latter by bringing people and producers from rural and urban areas together. direct contact between producer and consumer is important: it gives recognition to the producer, teaches the consumer about food and who it comes from, and builds trust in the food system. "food is not a commodity," he noted, "it is not something you just buy. it is something people grow, buy, and cook." his markets are designed to not just be places where people can buy and sell products but also places where traditions and stories can be exchanged and kept alive.

inaki aizpitarte (chef at le chateaubriand and le dauphin, paris)

rené mosse (winemaker, domaine mosse)

coquina et naturali vinorum

culinary inspiration can come from anywhere. for inaki aizpitarte, inspiration comes from wine, particularly natural wines that are different, that are not homogeneous. these wines express the flavour of a place and what the winemaker loves. natural wines, winemaker rené mosse said, require the winemaker to accommodate the native yeasts and unpredictable conditions, to trust and act in the moment. the tension between control and uncertainty is part of what makes natural wine interesting. aizpitarte picks up on this tension and responds to it when he develops a new dish. he illustrated this with a dish of "risotto" made with rice grain-sized pieces of samphire in a parsley puree, served with mosse's les bonnes blanches, a white anjou from the loire made with grapes grown in rocky ground filled with schist and quartz. the parsley and the salt of the samphire recall the familiarity of moules marinieres, but with a noticeable and unfamiliar set of flavours mixed in. these flavours echo the minerality, acidity, and wild nuances of the natural wine. aizpitarte said, "without wines like this, my food would not exist."

thomas harttung (founder, aarstiderne organic community supported agriculture)

urban food systems

thomas harttung sees urbanisation is an opportunity to rethink how our food supplies work. he estimates that an urban area the size of metro new york can produce 3mm tons of food per year. 50 new york metro areas worth of agricultural land are converted into cities each year. smallholder agriculture (which is well-suited to urban environments) is close to the world average for agricultural productivity and requires far fewer energy-intensive inputs like fertilisers and pesticides. small-footprint agricultural methods using man-made enriched soils would support this kind of urban agriculture. these methods were developed thousands of years ago in the pre-columbian period to grow food for dense populations of humans in the poor soil of the amazon. urban agriculture could be an elegant part of the solution to the food supply problem: the technology is already available, it doesn't compete with industrial agriculture for space, transport costs would be minimal, and small plots are conducive to extremely (and deliciously) diverse production. urbanisation, harttung argued, isn't going away so we should work to make urban agriculture a significant contributor to the food system instead of focusing only on expanding industrial agriculture.

magnus nilsson (chef at fäviken magasinet, åre)

fäviken: how we do the things we do

at fäviken in northern sweden, magnus nilsson and his staff are learning how to accommodate the seasons as they forage and grow their products, then use up what they have foraged and grown. he showed the beginnings of their research over the last few years. nilsson described the task of running faviken as cooking by gradually deciphering the relationship between four puzzles: 1) what can be foraged when?, 2) what can be grown when and how to grow it?, 3) what can be stored and how to store it? they have begun to develop a sense of a time map of foods they can get from the wild, from their fields, and from storage. a major ongoing project is to experiment with different methods of cultivation to identify the ones which remain in equilibrium for the very long term: in other words, methods that produce enough food for the restaurant while also not depleting the nutrients in the soil. their priorities are flavour and sustainability, rather than productivity alone, so they have rejected very productive methods in favour of apparently less efficient ways of growing their vegetables. they are also refining techniques for preserving and storing foods. this means finding ways--such as salting, smoking, drying, pickling, and others--to make fresh foods last longer without the texture and flavour disruption of freezing them. he gave as an example a method of storing leeks in near-suspended animation by keeping them in sand at 90-95% humidity just below freezing temperature. but their exploration of storage methods also means acknowledging that stored and preserved foods are not the same as fresh ones and developing ways of cooking them that reflect that. nilsson notes that "at base, we have to make choices and tradeoffs in the food we prepare. at fäviken, we're just trying to understand what the consequences of our choices are so we can act more intelligently."

jacqueline mcglade (executive director, european environmental agency)

copenhagen is buzzing: bees, cities, and our common future

colony collapse disorder wipes out entire bee populations and is increasingly prevalent, jacqueline mcglade said. this is a problem that concerns everyone since much of our food supply now relies either indirectly or directly on bee pollination: no bees, and very soon, no food. the problem has two major components: increasing use of pesticides in agriculture and low-diversity agriculture in which a small number of crops are grown over large expanses of land. bees are susceptible to pesticides, and low-diversity agriculture deprives bees of the opportunity to find crops that have a lower pesticide load. though bees are crucial to agriculture, our existing system of agriculture is killing off the bees it depends on. beyond their importance to our food supply, bees are like the canary in the coal mine. what is happening to bee colonies now may soon begin to happen to humans too. even in the most remote regions lacking intensive agriculture or industry humans already carry in their bodies significant amounts of heavy metals from the air they breathe, and the water and food they consume. to make things worse, consumers don't have enough information to make informed choices about the pollutants in the foods they buy. within the next year, mcglade said, the EEA will be aggressively pursuing companies and facilities that are egregious polluters and expanding an air and water quality information service called eye on earth to reduce this information asymmetry.

ben shewry (chef at attica, melbourne)

the cycle of love

at his melbourne restaurant, ben shewry's food reflects the care and questioning, inquiring approach that are the foundations of his cooking. questioning the taken-for-granted can produce more elegant, innovative, and sustainable ways of cooking. shewry began using plants foraged from urban environments before the practice became popular. "i never feel richer," he said, "than when i'm feasting on the scraps of society." as he learned more about the edible plants that grow in urban areas, he realised that foraging in urban areas is elegant because it solves many problems at once: foraging provides chefs and cooks with a source of diverse ingredients, encourages people to take care of places where they forage, and offers a chance to target invasive (but edible and tasty) species that would otherwise crowd out native plants. shewry also questions the assumption that a young country like australia has a short culinary history, and looks to indigenous cultures for inspiration in his cooking. this approach has led him to develop novel cooking techniques such as earth ovens based on maori practices from new zealand and discover new ingredients like corn cured in running river water (another maori technique). for shewry the strongest motivation for a questioning approach to food is its ability to help us learn how to stop making poor choices that result in unsustainable food and re-learn how to accommodate the world rather than imposing ourselves on it. questioning provides knowledge, and "knowledge combined with care can make food taste better," shewry said, "our responsibility as chefs is to know and to act."

other posts about planting thoughts:

planting thoughts: a symposium without dissenting views,

summaries: session 1, session 3, session 4

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: agriculture, complexity, copenhagen, execution success, food, planting thoughts, sustainability, technology, theory

infinite or merely enormous

Any particular event that we might wish to explain stands at the end of a long and complicated causal history. We might imagine a world where causal histories are short and simple; but in the world as we know it, the only question is whether they are infinite or merely enormous.david lewis, philosophical papers(ii; 214)

Posted by

vaughn tan

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: books, complexity, history, sociology, theory

luciferous, not lucriferous

Being a bachelor, and through God's bounty furnished with a competent estate for a younger brother, and freed from any ambition to leave my heirs rich, I had no need to pursue lucriferous experiments, to which I so much preferred luciferous ones, that I had a kind of ambition ... of being able to say, that I cultivated chemistry with a disinterested mind.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: books, decisions, epistemology, execution success, intransigence

Sep 7, 2011

Sep 1, 2011

planting thoughts: session 1, saturday a.m., 8/27

early on saturday morning, a storm comes into copenhagen. though it stops after only an hour, by then the field of flowers in central copenhagen where the MAD food camp raised its tents has turned into a sea of mud. off in a corner of the field, the red and blue circus tent that houses the symposium titled "planting thoughts" has partly collapsed. by 9am, the sun and the danish mosquitoes appear. some of the most world's most thoughtful chefs, writers, and thinkers about food, few of whom have appropriate footwear, stand in the mud eating bread, cheese, and danish pastries while workers, heard but unseen, struggle to repair the tent.

it's a difficult start to a symposium designed to be difficult. planting thoughts is about learning to question preconceptions about food and, in the process, going into unfamiliar and uncomfortable waters. david chang commented the night before that "this is unprecedented. nothing like this has happened before." so when rene redzepi gets onto the stage in mud-spattered boots to open the conference, the first thing he does is admit to being nervous: "i had the same feeling in my stomach when i started noma. it's a feeling in your stomach, your skin, your hair, everywhere." the kind of feeling you get when you start down a path and you don't know where exactly it leads but you sense that it may be taking you where you want to go.

when noma opened, denmark was a protestant country where food could never be cuisine. "our protestant culture was about quickly eating boring food in silence. spices were always from out there, from somewhere exotic where the people are brown and the sun shines all the time. but we found them right here under our noses." for them, noma was the start of the cascade of good things that happen when people find each other and realise they care about the same thing in different ways. "delicious food can be made anywhere," they realised, by learning who to work with, what foods are available, when to buy it, and how to cook it. to be constantly questioning is hard and uncomfortable work but because of it, rene pointed out, "the world opens up. everything is possible. and even if it isn't, we have to try."

tor nørretranders (author and philosopher of science)

from wild to tame—and back again

satoyama and reconstruction after the earthquake

other posts about planting thoughts:

planting thoughts: a symposium without dissenting views,

summaries: session 2, session 3, session 4

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: agriculture, complexity, copenhagen, epistemology, food, history, planting thoughts

walking house and flower dome

what you see outside the nordic food lab's boat. the house seems to move every day or two. no one knows why.

Posted by

vaughn tan

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: copenhagen

Aug 30, 2011

planting thoughts: a symposium without dissenting views

[the article about planting thoughts that i wrote for the atlantic is here.]

i spent last weekend in copenhagen for planting thoughts, a symposium primarily for chefs and other people connected to the food world and designed to stimulate new thinking about the food producer's role in the food system. in many ways, this was rene redzepi's brainchild, born out of a conviction that good food is important enough to warrant effort, serious discussion, and questioning. the list of speakers they'd managed to assemble was impressively diverse and accomplished, and all of them shared this basic conviction. but partway through the first session of speakers, i developed a sense of unease which grew as i listened to both the presenters and the audience over the course of the symposium.

don't misunderstand: i've never seen a group so committed to thinking about food in nuanced ways and so able to express what it is that drives them to cook and makes them cook the food they do. what's troubling is that the symposium's speakers and audience mostly spoke with one voice and one mind. i heard almost no dissenting opinions about the value of good food.

during the lunch break, i got to talking with christian nedergaard from ved stranden. he pointed out that everyone at the symposium has made sacrifices for good food but that none of the speakers had a good solution for those for whom those sacrifices don't even appear to be an option. at the end of the first day, i messaged a question to rene, who was taking questions for speakers via twitter. he asked them: "what advice can speakers give to people who don't think they have enough time to find or cook good, real food?" there was an awkward silence. finally, rene said, almost helplessly, "there is no short cut or easy answer to good food." then kamal mouzawak, who runs a farmers market program in lebanon, took up the microphone to disagree. "there's no fuss," he said "you just need access to good food. stop watching cooking shows and start cooking." and the tent erupted in applause.

i found myself nodding reflexively, with everyone around me, in response to kamal because i'm the guy who arranges meetings around his bread baking schedule because otherwise i'd have to go to brookline to buy a baguette that doesn't have a crumb the texture of a pullman loaf. i'm willing to put some money down that most people in the tent this weekend are similar. they've spent lots of effort deciding for themselves what food counts as good. maybe they take the occasional short cut and eat a microwave pizza, but they don't do it often.

but millions of people don't think they have enough time to find or cook good, real food, or that good food is worth the effort. you can't get around that. what rene said contains a hard truth, maybe the only really hard truth in food: good food is nothing but fuss and effort, often for many people. you eat a perfect grilled sardine and you have to thank the fisherman who makes less money because he fishes responsibly and avoids bycatch when he fishes for sardines. and if you didn't buy your sardines at the docks, you have to thank the fishmonger who ate the cost of yesterday's unsold sardines rather than sell them to you. and if you didn't cook the sardines yourself, you have to thank the prep cook who took the time to scale and gut the fish carefully so the stomach doesn't break (it's bitter), the grill guy who gave it just enough char without burning it. everyone who brought you that grilled sardine was free to choose: the fisherman didn't have to fish responsibly, the fishmonger didn't have to sell only impeccably fresh fish, the prep cook did not have to spend that extra 4 seconds gutting the fish carefully.

when we make choices about the food we cook and eat, we decide based on what we value and what we don't. deciding what to value means asking the really hard questions: what makes food "good" or, for that matter, "real"? if you have to choose between spending time playing with your child and spending time so she can eat good, real food, which should you choose? these questions cannot be asked and meaningfully discussed in a room full of people who believe at base in the same set of values.

nevertheless, planting thoughts brought together over 300 people, chefs and non-chefs, many working at the very edge of the innovative top end of cuisine around the world, and gave them many examples of the myriad definitions people have of "real" and "good" food. this is a staggering achievement. even at the high end of cuisine, critical discourse about values in food is the exception, not the rule. planting thoughts is a much-needed start. massive change begins when we find others who share the same ideas and values. the next step, a crucial one, will be to bring into the discussion the millions of people who--for whatever reason--don't share the premise that good food is worth the considerable effort it takes.

summaries: session 1, session 2, session 3, session 4.

Posted by

vaughn tan

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Labels: copenhagen, execution success, food, planting thoughts